For most Americans, World War II is only a lesson found in a dusty history textbook.

But to Tom Dimperio, 94, of Ceres, the war to fight Adolf Hitler's advances in Europe is as close as the piece of Nazi mortar shrapnel lodged behind his left ear, a wide scar on his chest, a left arm shortened and mangled by a German bullet and disturbing memories of comrades dropped by battlefield artillery.

"We trained together for over a year and a lot of troops, we became the best of friends just like brothers," said Dimperio. "And one day you'd see John get killed. The next day you'd see Joe get killed. And you know, my turn is next."

Such experiences are hard to get over, said Dimperio, whose 5-foot-2 frame belies the giant of a war hero inside.

"It takes everything out. You lose all hope, you wonder why this is happening. I'm still haunted. I still dream about it."

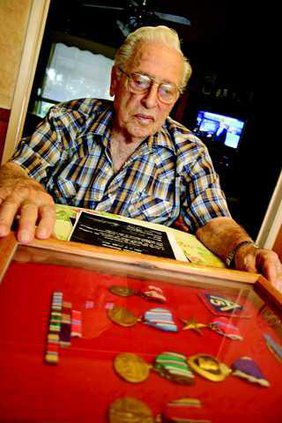

Wounded twice in battle, Purple Hearts testify to his bravery but fail to tell the story of what he lived through and how he survived what he did.

"Somebody was with me," he said, craning his neck with his eyes peering beyond the ceiling.

Before relating his war experiences, however, the amiable Wallen Way resident recounts how the Dimperio family ended up in Ceres nearly 90 years ago. His Italian immigrant parents, Luigi and Lena Dimperio, brought him to California from Hoboken, N.J. where he was born on Aug. 18, 1919. Dad chose San Francisco when Tom was five months old. Luigi found work there and lasted five years in the big city but felt a call to get back to farming he knew as a young man. The Dimperios found a 21-acre ranch on Richland Avenue in Ceres (the house still stands at 941 Richland) which they bought in 1925 for $9,000. They grew wine grapes, walnuts and a family.

Tom led a quiet life, attending Ceres Grammar School (Whitmore School) where he graduated eighth grade in 1934. He remembers being paddled by both teacher Mae Hensley and principal Walter White. Schools, of course, were named for both.

"She spanked me one time. I was smart-mouthing, I guess. Walter White hit me one time too. He had a razor strap and he used that on me one time. It was two or three lashes. It didn't draw any blood."

He remembers classmate Carlton Broadwell, who later became Stanislaus County assessor, being taken into the classroom closet for a paddling by sixth-grade teacher Evelyn Mashek.

Dimperio was a member of the Ceres High School class of 1938 but did earn his diploma until after the war.

Before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government was drafting young men for military service. Dimperio's draft number was called up but a heart murmur earned him 4-F status. When the U.S. was plunged into war, Dimperio was called back and classified as 1-A and inducted into the Army on Nov. 19, 1942.

"I hated the idea of having to go in the Army but once I got into it I got along real good. I liked it."

Tom went to Camp Gruber in Oklahoma in December 1942 for basic training until June 1943. He was then sent for combat training in Louisiana for three months. After that was Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.

Assigned to the Fifth Army 88th Infantry Division, Dimperio's journey to war started aboard a troop ship to Casa Blanca, North Africa, arriving on Christmas Day 1943. After months of mountain training, he and his comrades were sent to Naples, Italy in February 1944. Hitler had invaded Italy on Oct. 9, 1943 and advanced to Rome.

March 1944 was the first time the Ceres native saw combat. He was 24 and scared.

"We relieved the British Army," recalled Dimperio. "The Italians had surrendered before we got there so we were fighting strictly just the Germans."

By April 6, Allied Forces had entered Rome to take it back.

He engaged in limited gunfire but it's just as well that Tom never actually witnessed any of the enemy dropping from his bullets.

"We would shoot at the enemy but I never actually saw one fall from my shooting. Because every time we got into combat there'd be more than one of us shooting at the same target so we never knew which one got who. I couldn't say, ‘Well, I got that one.' "

The Americans camped out between Naples and Monte Casino in Italy before the "big move." It was on May 5, 1944 in Castle Forte, Italy, that Dimperio was wounded when a Nazi mortar shell landed nearby. He was struck by seven pieces of shrapnel.

"One piece is still embedded in the bone behind my left ear," said Dimperio.

He healed fairly quickly and rejoined his company on July 3 to engage in various squirmishes.

Tom Dimperio's life would forever change on Oct. 2, 1944. During a charge on the Nazi's soldiers between Florence and Bologna, Dimperio and company rose over a hill and started down the slope.

"Of course, the enemy was on the next hill waiting and the machine gun fire opened up," said Dimperio.

He remembers running with his rifle through a rain-soaked muddy field that had been plowed by a farmer.

Bullets were zinging past the Americans, including Dimperio. One machine gun round from a Nazi soldier struck the body of the Ceres native. He unbuttons his shirt to expose a long scar on his upper left chest where the bullet entered before exiting out the arm pit and smashing into his upper arm bone. The bullet completely shattered the bone in his arm.

Now seriously wounded and bleeding profusely, Dimperio continued running toward a level spot where there was a large pile of manure.

"I landed close enough to that pile of manure that I crawled up behind it. The guy that shot me saw where I fell and he kept shooting and I could hear those bullets plunking into that manure. Thank God it was big enough to where the bullets wouldn't go through. So let's say that a pile of manure actually saved my life."

Still down - his wounds would have been mortal had he not received medical attention quickly - Dimperio remembers blood pouring out of his sleeve.

"I laid there a few minutes. I knew I wouldn't live from the loss of blood so I decided to get up and get out alive or get finished."

From the moment he was downed, American troops had advanced to his location. Since the shooting stopped, Dimperio theorizes that the German who shot him had either bailed from a foxhole or had been taken out by return fire. Dimperio walked about 20 feet before collapsing and being scooped up by Army medics.

"They picked me up on a stretcher and took me back up over this hill where there was a medic station on the other side. Of course, my clothes were full of manure and mud and blood so they cut everything off."

He passed out, waking up in a field hospital with consciousness fading in and out from shock. A doctor informed him they were going to operate and offered him a shot of whiskey, which he accepted.

From the battlefield to America, medical care was not good. His arm became infected and would not heal.

"I was in the hospital for 25 months," said Dimperio, who noted that he visited nine different hospitals. He rode on a hospital ship to the United States that took 13 days.

"That's when this thing got infected because there was no medical care of any kind on the ship," he said.

Doctors operated as soon as he arrived in Charleston, S.C. A week later he was on a train bound for DeWitt General Hospital in Auburn, Calif. There Dr. Edward K. Prigge shook his head at the sight and observed that Tom had signs of yellow jaundice.

"There were several times I knew I wasn't going to make it," said Dimperio who woke up in a pool of blood after one surgery went bad in Auburn.

Doctors tried numerous surgeries to repair the arm and make it functional. They tried fusing the arm bones together but he didn't care like that and they took out inches of bone. To this day the two sections of arm bone are not connected, rendering the arm virtually useless for simple tasks like eating or dressing himself.

After months of hospitalization and now stable, Tom was able to leave the hospital on a pass and came to Modesto to buy a 1941 Ford convertible. One weekend he and a friend went to a downtown Auburn bar when they spotted two girls riding rented horses past the Freeman Hotel. Tom wanted to meet them and followed. One of the girls was Genevieve "Gene" Foster.

"I told everybody I liked the looks of the horse," said Dimperio with a grin.

Tom asked Genie out for a burger but she turned him down. It was not until they met later that she agreed to go on a date. Closure of the Auburn facility meant Tom would receive care at Birmingham General Hospital in Van Nuys.

He was discharged from the Army in November 1945.

Tom and Genie were married March 18, 1946. She brought into the union a son, David, from a previous marriage that lasted only a month since her husband was killed in an automobile crash. Together Tom and his bride had a son, Thomas, who is a retired clinical psychologist in Albuquerque.

After the war, Dimperio worked at the Texaco station in 1951 and 1952. He took a Civil Service exam to work at the post office. He was given a job in Modesto in 1952, retiring in 1978.

Those battlefield experiences taught Dimperio to despise war.

"With all these boys that are being killed, what for? World War II was supposed to be the war to end all wars. Has it ended all the wars? It never will."

Those experiences also changed him. One never goes forth from an experience like that unchanged.

Tom pulls out an old photo from his wallet. It's a photo of himself with two other men in Rome. The priest is only in the photo because he happened along and wanted to be included. Tom chokes up, however, when he recalls the friend on the other side of the photo whose first name now escapes him. He has trouble getting out the words.

"This is Jimenez," he said while pointing at the man in uniform. "After I rejoined my company (after the first wounding) we got back into combat and there was a German lookout house up on the hill and our squad was sent to take the building. And I saw Jimenez take a bullet right in the forehead. They were all just like brothers and when you see one get killed like that right beside you ... they didn't get me, they got him."

He watched another friend take a bullet into the face and blow out his teeth as enemy fire cut a path between his gums.

The war took its toll on Genie's family as well. Her brother, airman Jessee Pierce, was aboard a fully loaded B-29 bomber that took off from India for a Japanese bombing mission but the plane crashed. He died instantly.

As if he had not faced enough travails, Tom was seriously injured on June 25, 1967 when he and son David were riding in a car that was slammed head-on while en route to a car club rally on Tioga Pass outside of Yosemite National Park. Tom suffered a fractured skull and concussion and was in a lucid mental state for three weeks. David suffered a broken neck. Tom was given last rites from a Catholic priest but, like on a European battlefield, he defied the odds.

Today Dimperio is a member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Legion, Purple Heart Foundation and Disabled Veterans of America.